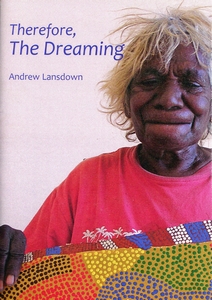

THEREFORE, THE DREAMING

Andrew Lansdown

Life Ministries, 2017

(poems & stories, 32 pages)

PRICE: $5.95 (free postage)

This short collection contains ten poems and two short stories dealing with Australian Aboriginal themes/subjects.

The title poem is reproduced below:

Far from Home, the Blower

Close off one end of the didgeridoo

and look down the other—

that’s how black he is, this Kimberley man.

He has come to the school for the didgeridoo.

He wants to take it back to his cell,

but I cannot give him permission

immediately. This is a maximum security prison:

procedures must be observed. So

he is playing it now in the literacy room.

I tell the officers he will be staying

for the afternoon. He is playing it now.

His eyes are closed and he is tapping

the plastic seat with his thumbnail

as the pipe drones at his feet.

Abruptly, in a gesture of harmony,

he breaks his rhythm. That lillgah,

he says. I do not understand.

Lillgah, he says, slowly, several times.

I cannot get it right. Lillgah—like tuning.

Making didgeridoo same as singer.

He plays again. A singer silent to me

is chanting in the channels of his ear.

He listens, trying to match his music

to the key and rhythm of the voice.

We always do this, start

with lillgah. If the singer not happy

with one blower, he get another.

Me a deep blower. He blows again. Indeed

the drone is deep. But I never knew

it could be otherwise. Some singers are high.

You know? Clear. He throws his head back,

taps his throat, and sings—high, nasally,

rhythmic, in ‘language’.

I know this singing, but its meaning

is ancient and alien. He is singing

and we are in harmony. I do not

ask for meanings. But I say,

Sing low then, Simon. And he sings

low and husky, unlike anything

I have heard before. The blower

must be the same. See?

He plays again. A different rhythm.

An officer comes in, jangling

his keys. O freedom! I do not look up.

The didgeridoo drones vibrantly,

striking up a resonance in my soul.

Taut or slack, spiritual chords

are strung across the hollow

at the heart of every man.

No man is mere matter—therefore

the Dreaming. ‘Kudda, brother,’

one of the tribal men from Kalgoorlie way

calls me. A man from Noonkanbah Station

greets me behind these walls as ‘Papaji,

brother.’ Simon does not call me ‘brother’,

but he is playing the didgeridoo

for me. He breaks off suddenly. Now

the young girls come in. Jdirree-jdirree.

He flicks his hands, makes a few staccato

movements with his torso. Wanga.

That the Law. The women start first.

He begins again, the familiar droning

tempered by new rhythms and sounds.

And somewhere in the didgeridoo

a brolga begins to dance and cry.

The men this time. First the brolga

dance. He stops again. Now

a dingo. She crying for her pup. And

distant through the droning, a dingo

barks and howls in the hollow

of the didgeridoo. When I was initiated …

He is rehearsing his life.

And I am a cut and ochred

hollow branch: he speaks into me

evoking a sympathy that, in turn, stirs

his heart to a symphony of longing.

When I am made a man, the blower

he’s playing all day. Never stop.

He be giving me his wind.

And they give me a didgeridoo, to be

a blower. But I never play

all day for initiation. I never be picked

to play all night for corroboree.

I only play short time. For fun.

You know? Maybe for white people too.

For fun. Like frogs. Gningi-gningi.

I can’t catch the words.

He is sharing unfamiliar things

in a voice too quiet and quick. A good blower,

he cut his tongue with spinifex.

He pokes out his tongue. It is very pink

against his purple lips. He runs his thumbnail

down the tip. Yours cut? I ask.

No. Too fat. But good blower,

he listens. He hears. He gets the wisdom of it.

He cuts his tongue, gets plenty sounds.

Plenty wind. Like tortoise. Like crocodile.

You know? His gaze is distant.

He is dreaming. To be a blower,

he says, to be a didgeridoo-man

is good. You know? Get respect. Get proudness.

© Andrew Lansdown