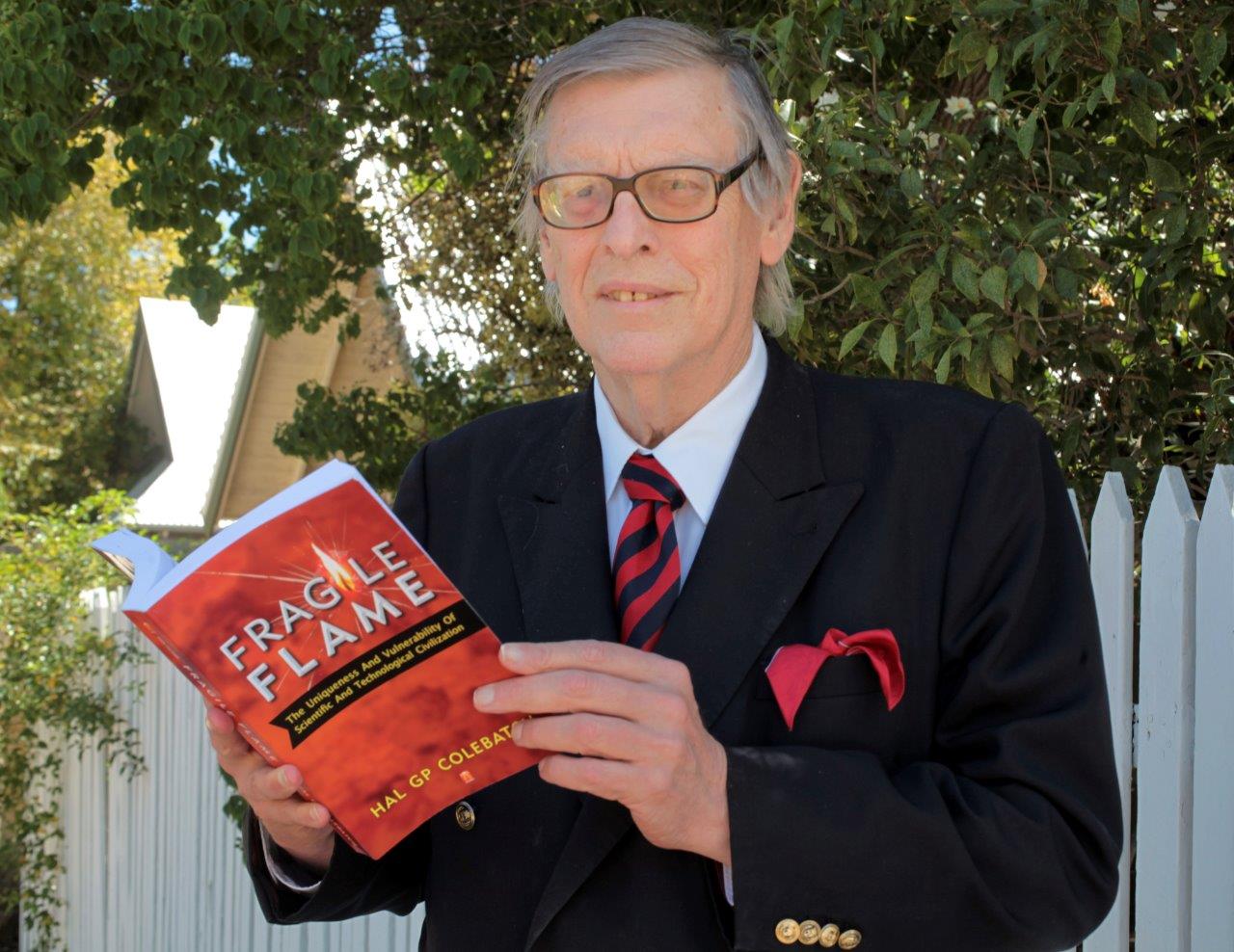

Hal Colebatch – Photo: Billie Fairclough, POST Newspapers Pty Ltd

Six poems by Hal G.P. Colebatch

1. Autumn Morning

2. Dinghy Sailing

3. Weeding the Garden by Moonlight

4. Climbing

5. 11 September, 2001

6. Photograph of a Bristol University Ceremony, 1941

7. Beaten

8. Can the Dead Forgive

See also biographical and bibliographical information further down this page.

Click here to read Andrew’s review of Colebatch’s Return of the Heroes.

Hal Colebatch died on 9 September 2019. Click here to read Andrew’s memorial service tribute to him.

Read Andrew’s tribute poem for Hal Colebatch, “Vikings”, on this website here.

Autumn Morning

The jetty is deserted in the sun. Warm light

streams to the river-bed, catching

the lines of feeding fish, bright

on the warm sand, seen clearly through

unruffled water, their movements matching

the slow currents, threading the new

growth over tyres, cables, cans, all shown

lying still in growing weed, changing fast

into the stuff of the river. Bars of gold sun

fall on them, holding the shrimps, the mussel shells,

the lives all overlooked. Martins dart past

to their nests under the boarding. The morning smells

of sea air, and new-mown grass, as ripples run

on this calm day. Even those cans and tyres

are full of life, each harbours its own crew

of living things. Ripples like cool fires

wander the sunlit surface, lines blown

by some unfelt wind. At the shore a few

people are wading. A few dogs and children run

on nearby grass. Over its little commonwealth of lives

of the hardly interesting, the marginal, the small,

the hardly beautiful, itself part of them all

and happily ignored, where so much thrives

the jetty stands deserted in the sun.

from The Light River

© Hal Colebatch

Dinghy Sailing

It must be hard to sail a boat without wonder,

a pure, childlike wonder at small things:

the colours of shallows over mud-banks, the wings

of cormorants drying on spit-posts, crabs going under

rocks, or simply blue spray and a sail full of air.

And it is impossible to sail without knowing

of breaking-strains, and that just so much wind

can capsize a dinghy, and that nowhere

for all the simple beauty and all the showing

of freedom, is there any smallest estuary you can blind

with non-science, or lie to. Therefore when

I see men sailing dinghies there seem to be

with them and whispering at the last edge of the sea

clear shadows of much earlier men.

from The Light River

© Hal Colebatch

Weeding the Garden by Moonlight

I have barely started these nocturnal labours

when the local cats come: first the neighbours’

fluffy white kitten bumps me with her nose.

Ginger Sheba, a ghost tiger, weaves and flows

between the stalks, and little black Felix

stares down from the eaves as Calico One licks

and preens against my legs and hand.

What is it brings this multi-coloured little band

of pirates and cupboard-lovers in the moon-glow

to watch me weed? What fascinates them so?

They put aside their complex games and stare

at what I do, moon-eyed like lynxes in some lair.

Is there some echo of Eden in this scene:

animals watching a man make things as they might have been?

from The Light River

© Hal Colebatch

Climbing

The German battleship Tirpitz capsized after being bombed in a Norwegian fjord late in World War II. Several hundred of the crew perished in the upturned hull. About 85 climbed up through the ship to the inner bottom, and were rescued.

Upward. Freezing we climb in this freezing dark,

upward between torn steel as batteries die,

between the whittering waterfalls, the stark

madness that rushes from the steel inverted sky.

How can we be under these black steel facts?

How can we think upon our coming home

in this madness of oil and ice and cataracts,

black but for mincing pin-points in the rush of foam?

In this smashed world, this torn empire

off uniform steel and iron, moulded men?

Climb now, between the hammer-strokes

of falling machinery, between men dying again

in shut, filling compartments, with rolling steel

— this is a second death, this black freezing time,

when all is destroyed, save flickering lights that feel

the freezing waterfalls and weep and climb.

Climb. Upward and climb. Grip oily icy steel,

grip now and climb and think and do not think.

Hope and despair are one, with us who hold

now after Judgement Day, now fallen past any brink.

Upward. We must simply starkly hold

what resources we have, between with waterfalls.

Survive. Survive the oil and fire and cold,

the clanging blackness where the last madness calls.

Through each next hatchway to the crazed black sky

of armoured steel that seals us freezing down

under these roaring waterfalls. So we will try

as machinery falls and one by one we drown.

We are already dead. We have no wreaths or sagas,

or know what fire or waves may roll above the steel.

Our world is gone to ruin, our world is crushed

to black freezing oil, to water we now hardly feel

fingering our ankles and heels as we climb,

clutching us back. But we may not admit we are dead

who are caught in this black Hell outside of time

If we have died, can we think on what lies ahead?

To climb. Only to climb up through this dark

leaderless, driven towards a desperate goal

with barely pride and courage, with one bare hope:

In a wrecked world, we will keep something whole.

from The Light River

© Hal Colebatch

11 SEPTEMBER, 2001

After the seminar my wife suggested

we walk home along the river-bank.

Shells sparkled

at the edge of the river’s green,

sand-banks rising to gold, changing

with the reflected patterns of cloud.

We watched a boat being varnished

and when we stopped at a jetty restaurant for coffee

pelicans gathered round.

from The Light River

© Hal Colebatch

PHOTOGRAPH OF A BRISTOL UNIVERSITY CEREMONY, 1941

I went down to Bristol to receive a degree at the hands of the Chancellor, Mr Winston Churchill … During the previous evening the Great Hall of the University was destroyed. When we arrived the ruins were smoking; there was wreckage everywhere. Members of the faculties arrived wearing their academic robes over their smoke-stained battledress. – Robert Menzies, Prime Minister of Australia, Diary.

Radiant smiles. Two men in archaic robes

In a burning city. Just out of sight

Rescuers dig through rubble. The bombers

Will be back again that night.

And behind those grins? We know they know

barring some miracle, the end is near.

The options have come down to little more

than to smile and wave, and not show fear.

Nearby, they know, the Home Guard drill

with brooms and shot-guns. That is all

there is left to do. The smoke-clouds drift

from the wreckage of the city, from the hall.

But the photographs may cheer some refugee,

Some soldier standing in a lonely breach,

Some mother, fireman, factory worker –

Robes and grins are weapons now, like speech.

About the only weapons. “Last hope island”

The Polish airmen call it. Who knows when

The end will come, the last hope drown in blood.

Gestures are left. Give them a gesture then.

In Poland the death-trains roll to East and West.

Smile for the cameras, leaders! Never betray

The anguish and despair beneath the smiles.

We have made a new Doctor of the Laws today,

Confronting all the modern age in arms.

A ridiculous, hopeless gesture at the dark.

The money and the guns are running out.

There are no allies now: the stark

and towering facts behind the grins.

Tired, fallible men, strutting in fine dress,

radiating hope upon the ramparts

of an old fortress, empty more or less.

Each moment now the sun is sliding

down towards the horror of the night.

But pretend that civilization has a chance,

make a good ending in a hopeless fight.

from The Age of Revolution

© Hal Colebatch

Beaten

It seems I have beaten

The horrible bowed bald grey skeleton-like thing

That lived in my hospital bathroom

Just above the wash-basin.

© Hal Colebatch

Can the dead forgive?

Can the dead forgive?

The question comes unwanted

When the lights go out.

© Hal Colebatch

More information about Hal Colebatch

Hal GP Colebatch has five degrees including a PhD in Political Science. In 2003 he was awarded an Australian Centenary Medal for services to poetry, writing, law and political commentary, the only award for this combination of activities. His poetry collectioin The Light River won the WA Premier’s award for poetry in 2007. He has had 7 collections of poetry published and 13 stories totalling about 450,000 words in the science-fiction series The Man-Kzin Wars, published by US science-fiction major Baen Books under the editorship of multi-Hugo and Nebula-winning author Larry Niven. He has also had short stories and radio dramas published. He has been described by Peter Alexander, Professor of English at the University of New South Wales, as among Australia’s best writers.

Hal GP Colebatch has five degrees including a PhD in Political Science. In 2003 he was awarded an Australian Centenary Medal for services to poetry, writing, law and political commentary, the only award for this combination of activities. His poetry collectioin The Light River won the WA Premier’s award for poetry in 2007. He has had 7 collections of poetry published and 13 stories totalling about 450,000 words in the science-fiction series The Man-Kzin Wars, published by US science-fiction major Baen Books under the editorship of multi-Hugo and Nebula-winning author Larry Niven. He has also had short stories and radio dramas published. He has been described by Peter Alexander, Professor of English at the University of New South Wales, as among Australia’s best writers.

Click here to read Andrew’s review of Hal Colebatch’s Return of the Heroes

Books by Hal G.P. Colebatch

POETRY

1. Spectators On the Shore

2. In Breaking Waves

3. Outer Charting

4. Primary Loyalties (with Peter Kocan and Andrew Lansdown)

5. The Earthquake Lands

6. The Stonehenge Syndrome

7. The Light River

8. The Age of Revolution

NOVELS

1. Time Machine: Troopers

2. Counterstrike

SCIENCE FICTION STORIES AND NOVELLAS IN THE MAN-KZIN WARS SERIES

(in chronological order)

1. The Colonel’s Tiger (MK VII)

2. Telepath’s Dance (MK VIII)

3. One war for Wunderland (MK X)

4. The Trooper and the Triangle (MK XII)

5. The Corporal in the Caves (MK X)

6. His Sergeants’ Honour (MK IX)

7. Music Box (MK X)

8. Three at Table (MK XI)

9. Grossgeister Swamp (MK XI)

10. Catspaws (MK XI)

11. Foreign Legion (MK XII, With M.J. Harrington)

12. Peter Robinson (MK X)

13. String (MK XII, with M. J. Harrington)

RADIO DRAMAS

1. Admiral Harvey

2. Lord of the Californian

OTHER

1. Return of the Heroes: The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, Harry Potter and Social Conflict

2. Caverns of Magic: Caves in Myth and Imagination

The Light River

(Poetry)

Hal Colebatch

Foreword by Les Murray

Connor Court Publishing, 2007

ISBN: 0-980293642

Winner (Poetry) – 2007 Western Australian Premier’s Book Awards

Judge’s Reprt – Colebatch is one of those versatile literary voices that our 21st century society needs – celebrating both the utterly local, such as the minute glory of shells on Rottnest shores, and the distant ‘scream of jet fighters’ above the hills of Lebanon. As Les Murray says in his foreword, this collection is ‘more tranquil than some of his earlier ones’. It is indeed a ‘light river’ rather than the polemical white-water raftings that Colebatch has sometimes released. Even so, in ‘The Heroes’ he savages a couple of Australian ex-prime ministers. Colebatch, who in his day jobs as lawyer and media commentator is usually restrained by verbal decorum, can be virulent in verse. Calming down again, he is an assured host, inviting us to share his praise for St. Paul’s Cathedral in London and for more ephemeral high points such as para-sailers soaring above the Swan River.

ARCHBISHOP HICKEY’S SPEECH

AT THE LAUNCHING OF THE LIGHT RIVER

BOOK LAUNCH – THE LIGHT RIVER – by Hal Colebatch

This is a benign book, a gentle book, one to read slowly with ears and heart open to receive the pictures painted through the words of one who can bring the best out of the English language.

Anyone who knows Hal Colebatch will know that his words are not always benign. He more than occasionally lines up his targets and lets the words fly like penetrating arrows.

This is a different book. It is Hal in a more introspective mood, conscious of the beauty of ordinary things and aware of the little cameos of elegance and charm that he sees in nature or even in a cat.

Hal writes about cats in this little book. Perhaps he has a special interest in cats, an admiration for their qualities of apparent contemplation and aloof superiority. Cats often look thoughtful, and wrap themselves in a deep meditative trance as they close their eyes before the winter fire. It may be that thoughts are just too much for their small brain, but they fool us all with their show of philosophical profundity.

May I quote? (Summer Morning p.64)

“… patrolling Winston and his small compass of whiskers and his purring buzz-saw that seeks to hold a mystery” (p.28)

The Light River, called, I presume after the shimmering Swan River, asks us to look again at familiar things and places, beautiful experiences in Kalgoorlie, Rottnest, Nedlands, along the river at Nedlands, and Augusta to name a few. He even takes us to the England he delights in, to Egypt and to Israel and to Lebanon.

This book is full of phrases that take you by surprise, as poets do. On Augusta he writes: (p.30)

Arriving late at night,

in rain and wind, just catching

the last toasted sandwich in the bar, to sleep

in a room wrapped in black wind …

Who of us would ever think of calling the wind a “black wind”, yet the word is just right in describing the sensation/listening at night to the rain and howling wind outside.

Of course the book contains more than beautiful lyrical poems and also of his own Haiku. This is a long epic poem about the fate of a cargo ship, the tanker called the San Demetrio. It is set in 1940, in the North Atlantic during the war, when it found itself caught up in a naval battle.

I launched out on the poem, thinking to read it in stages, but once I began I could not stop till I had finished it, so powerful was the language and the dramatic and relentless pace of the story.

There was no blame in this poem, no criticism of the actions of the hostile battleships in firing their destructive artillery, no condemnation of war that caused such pain, destruction and death, only admiration for the courage of ordinary people faced with the slim challenges of survival. They were not admirals or generals or trained fighters, these people were, in his words “mostly anonymous, dressed in dungarees, serge oil-stained tropic whites doing a fairly dirty job”.

“Mr Pollard, who has something to do with the engines,

“Mr McNeil, the Scottish seaman, there is Boyle, a little man who mixes engine-grease and wipes machines.” And so on.

What the poem does is show the nobility under enormous pressure and the threat of death, and the great courage of ordinary people.

This book of poems will please ordinary people like us because the poet takes us to ordinary places and shows us ordinary things, revealing their beauty.

If there is perhaps a hint that he is asking us to think about the origin of all these beautiful things, as he dwells on dove shells on a Rottnest Beach. P.24

The beauty of the dove shell on the white sand, he says, “is no accident”.

It reminds me of the insight of the Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins in “God’s Grandeur” when he said.

and for all this, nature is never spent;

There lies the dearest freshness deep down in things….

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent World

broods with warm breast and with, ah!

Bright wings

I have great pleasure in launching this refreshing book “The Light River” and offer my personal congratulations.

Most Rev B J Hickey

Archbishop of Perth

25 June 2007

The Light River can be ordered from the publishers at:

http://www.connorcourt.com/catalog1/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=25&products_id=32

The Age of Revolution

(Poetry)

Hal Colebatch

Picaro Press, 2012

Pages: 16

COMMENTS ON PREVIOUS VOLUMES

OF POETRY BY HAL G.P. COLEBATCH

Spectators on the shore (Edwards and Shaw, Sydney, 1975, ISBN 85551-007-2) 85 pages.

Critical notices include: Douglas Stewart (Letter) “A delightful book, full of humour and originality and perception and poetry. It is such a enormous relief to come upon a genuine command of technique”; Professor Veronica Brady, Westerly (December, 1975): “There poems belong to the great tradition … I am reminded in fact of Conrad as well as Orwell … Ironic, visionary, finely-crafted, this is a remarkable first book of poems. It will be interesting, or perhaps more than interesting, a matter of life and death for us all, to see where Mr Colebatch will go from here, for his imagination, intent on the movement of history and our situation, may be an Early Warning System for us all.” See also Bruce Bennett, Editor, The Literature of Western Australia (University of Western Australia Press for the 150th Anniversary Celebrations, 1979), pp. 175-177.

In breaking waves (Hawthorne, Melbourne, 1979, ISBN 0-7256-0245-5), 74 pages.

Critical notices include: Douglas Stewart, The Sydney Morning Herald (5 January, 1980): “Hal Colebatch lives in Western Australia, and … may not be heard in Sydney as clearly as [he] deserves to be … a delightful poem, entitled “A song of the Prague Spring”, this poem is included in Colebatch’s new book and, as he walks and watches and thinks he way across Europe and south-east Asia … there are quite a few of similar quality. I must note among his virtues that he can turn a sonnet, even the difficult Petrachian form … which I thought only Robert D. Fitzgerald could do – exactly as it should be turned in modern times, sounding as if it were a completely natural utterance yet retaining in absolute correctness its traditional compactness and force … But after the Prague poem or equal with it, and not forgetting some striking and memorable poems of World War II, my favourite in “University Incident” … In Breaking Waves seems to me exceptionally capable, attractive and thoughtful. I am pleased to note that, in spite of the ominous note running through it, Colebatch still sees some hope for humanity.” Michael Thwaites Canberra Times, (May 31, 1980): “A vein of genial satire … tinged with surprise.”

Outer Charting (Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1985, ISBN 0-207-15127 X), 110 pages.

Critical notices include: Christopher Koch, The Sydney Morning Herald (24 August, 1985): “Hal Colebatch’s excellent collection does not disappoint one’s expectation of non-conformism. In his style and the content of his thinking and responses, he is his own man … the poems are often as arresting as good short stories: they grip … it is in the longer poems that Colebatch displays his real strength: at times he comes close to Larkin’s terrible simplicity … His tone ranges from appreciation to a moral indignation he serves up plain, and he is capable too of a wry and meditative irony as he contemplates the hard facts of the present ticking away under the surface of things …”; Bruce Beaver The Australian (31 August, 1985) … the content is always positive and colourful when not dramatising a darker issue);The West Australian (10 August, 1985) “The verse restores an emotional base for a world becoming increasingly concerned with the facts and insensitive to feelings … it is an endearing attitude, making the appearance of his poetry on the scene of everyday life as natural as other passages from the media. Poetry is forging ahead on the right tack when you can pass a copy of Outer Charting around the room and get an immediate sympathetic reaction.” Chris Wallace-Crabbe, Australian Book Review (December 1985-January 1986): “A poet who had sturdy intentions to broaden the scope of the art, to push it out into wide fields of politics, social satire, modern history;

The Earthquake Lands (Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1990, ISBN 0-207-16352-9), 60 pages.

Critical notices include: Geoff Page, Canberra Times (20 October, 1990) “Colebatch appreciates the whole sweep of history and the ironies it throws up. But more than such ironies he savours moments of unalloyed emotion, especially courage and that continuing determination to “hold the line.” Australian Book Review (1990): “A writer sure of his powers … The Wild is a source of both innocent wonder and an anachronistic code of honour …” Peter Kocan, Quadrant: “Even Colebatch’s bursts of ferocity (no Australian poet writes more scarifyingly in anger) are prompted by love of some lager ideal which is being denied or perverted … Colebatch is concerned with what might be called the heroism of duty, as against the heroism of Ego … And yet what gives Colebatch his fond affection for the human race is the fact that there is no automatic cut-off point between the heroic and the mundane …

The Stonehenge Syndrome (William Heinemann Australia, Melbourne, 1993, ISBN 0-85561-508-7), 100 pages.

Critical notices include: Peter Kocan Quadrant (October, 1993): “This fifth collection of Hal Colebatch’s poetry adds to a body of work as distinctive as any in Australian literature … He is in fact a Chesterton-type, an Orwell-type, a born knight-errant whose true quest is never quite the same thing as the smelly little orthodoxies which might claim to embody it … but the typical ringing note is celebration.” The West Australian, (28 August, 1993): “This is Colebatch at his best, gambolling on the edge of the precipice and then stopping short at the last moment to ponder the elusive mysteries … Moral positioning, of course, is bad form in our reprobate literary culture. Yet the role of all true writers is to cross out the mercenary estimate and to lay an inky trestle across the chaos to a happier life. The finer moments of The Stonehenge Syndrome manage nothing less”. The Australian (14-15 August, 1993): “Sense of wonder is terrifically well invoked.”

Primary Loyalties (With Peter Kocan and Andrew Lansdown) (Arawang, Canberra, 1999, ISBN 0646 37368 0), 60 pages, Colebatch pp. 7-24.

Critical notices include: Author and former editor of The Bulletin and Quadrant Peter Coleman (The Adelaide Review, September, 1999): “I warmly recommend … clear, rhythmical, passionate and traditional … the poems in this volume are all about the primary loyalties that help us through life … a pleasure to read Hal Colebatch …”

“Australia’s best writers include … Hal Colebatch.” Professor Peter Alexander.

.

.

Time Machine: Troopers

(Novel – Science Fiction)

Hal Colebatch

Acashic Publishing, 2011

ISBN: 978-1-4475-6091-3

Pages: 172

.

.

THE STORY OF THE SECOND JOURNEY IN TIME BY THE TIME TRAVELLER – FROM H. G. WELLS’S “THE TIME MACHINE”.

The Earth has always had two races, the Eloi and the Morlocks.

The Eloi, or surface dwellers, are a beautiful but weak and useless race, made soft and decadent, left to fatten. But now the Morlocks, the Underworlders, desire what they have hungered for, and come back to the surface of the planet at night, and begin to eat the Eloi. The Eloi are terrified of the night, of shadows and black things.

Feeling compelled and duty-bound, The Time-Traveler must return to the distant future of the Eloi and Morlocks to try to reinvigorate the Eloi and avenge the death of the Eloi girl he loved, Weena.

Deciding on the daring capable companion of General Baden-Powell, who will later found the Boy Scouts movement, they travel to the year 802,719 — gathering a group of Eloi in readiness for civil war. One which will see the Morlocks travel through time and pour into England through tunnels under the English Channel.

“A great battle is about to be fought against a more austere race of invading Morlocks. Hal Colebatch succeeds in making the sequel better than the first!” Coverage Report #758

BUY THIS NOVEL FROM THE PUBLISHERS HERE: http://www.acashic.com/counterstrike/

.

REVIEW

TIME MACHINE: TROOPERS IS DEEPER THAN WELLS

Time Machine: Troopers, by Hal Colebatch

(Acashic Publishing, 172 pages, $23.99 paper; $19.99 e-book)

In its own way, American Spectator contributor Hal Colebatch’s new novel, Time Machine: Troopers, is as subversive a book as any written in our time. What differentiates it from famous subversive novels like Candide, On the Road, and Catch-22 is that it’s subversive of the subversives, a counterrevolutionary romance.

How many of us have enjoyed books by authors like H. G. Wells, regretting even as we read the political and philosophical obtuseness underlying them? Colebatch tackles that problem hands on, revisiting the story and the characters in a more sensible and realistic (in terms of human nature) manner than Wells would ever have been able. The unnamed Time Traveler, in this book, says of Wells (who appears as a character):

I felt that under his optimism there was always a core of despair at the centre of his soul. As for the only way out he had looked to, “to live as if it were not so,” as if mere petty existence was all we would ever possess, I had thought such a doctrine of “existentialism” (as I called it for want of a better name) a mindlessly petty and bleak one. I am still prepared to wager that should such a view come to be held by the leading body of philosophers of any nation, that nation (though it be as great in the field as France… is today) would not any longer be able to control its affairs: an invader would sweep its defences away.

The ending of Wells’ book, the Time Traveler here informs us, was fictionalized. He did not, in fact, return straightaway to the future, never to be seen again. In fact he lingered in London, traumatized and depressed, contemplating the bleak vision of the future he had been granted. And gradually a new conviction grew on him — he had seen gratitude and courage in the Eloi woman Weena who had befriended him. What were the odds that this particular Eloi should be completely atypical of her people? Were the Eloi the helpless victims of evolution, or simply a population that had forgotten old lessons, lessons they could be taught anew?

In time he determines to return to the future world of Eloi and Morlock, but this time he will go prepared. He will bring with him tools and armaments, in order to help the Eloi care for and defend themselves.

He will also, he decides, need a companion, someone to watch his back. He considers a number of friends — Wells himself and young Winston Churchill among them. But he settles on a more suitable prospect, a recently returned general of the Boer War, Robert S.S. Baden-Powell, hero of Mafeking.

Baden-Powell, at this point, is not yet the founder of the Boy Scouts, but he already has some ideas along those lines.

The future world will be saved by Scouting.

(Tell me the truth. Have you ever read a more audacious concept for a novel?)

Through the adventures the Time Traveler and Baden-Powell experience in revisiting the future, Colebatch ruthlessly mines Wells’ own story for the inner contradictions that gainsay its author’s world view. Colebatch understands that good storytelling has its foundation in truth, and is ultimately incompatible with canting ideology. Wherever a ripping yarn is found, there an eternal verity is attempting to kick its way out.

The result is a whole lot of fun. This is the kind of story that used to be written (especially for boys), a rousing tale of courage and loyalty and hope. By writing in the voice of an Edwardian, Colebatch is free to unashamedly celebrate those manly and (dare I say?) English virtues that the world once admired and emulated, not so terribly long ago. And perhaps might again.

“We may be up against it, but remember, every Eloi, however small and weak, can Do His Best! We are going to teach Johnny Morlock a lesson he won’t forget in a hurry!” [says General Baden-Powell on the eve of battle.]

It takes considerable skill to carry this sort of thing off, I’ll grant, especially in a time like ours, but Hal Colebatch of Australia is the man for the job. You’ll smile as you read Time Machine: Troopers. You’ll want to give it to your son or your nephew. But you’ll keep a copy for yourself.

This review was published in The American Spectator and may be found here: http://spectator.org/archives/2011/05/13/time-machine-troopers-is-deepe

.

.

Counterstrike

(Novel – Science Fiction)

Hal Colebatch

Acashic Publishing, 2011

ISBN: 978-1-4475-6090-6

Pages: 245

.

.

WORLD WAR III IS LOOMING…

Harry has been trying to “get away from it all” for a long time, so he goes sailing to nearby islands with his friend Toby Bowen. They pass a University expedition searching for the wreck of HMAS “Darwin” which vanished in World War II. They meet a mutual friend, Monty, and a pair of beautiful women board Monty’s launch, and head for the Hesperides, a group of outlying rocky islands, barren and very seldom visited.

But a curious incident occurs that catapults them out of their idyllic setting and slaps them bang into the middle of a potential real world catastrophe.

On the way to the Hesperides they pass an old minesweeper, the Waroona, due to be “hulked.” Diving the reefs, Harry finds a naval gun in shallow water but does not tell the others because he is not sure what it signifies.

Soon it becomes clear that they have stumbled upon a plot by terrorist-supporting groups that will forever damage relations between Britain, America and Australia, unless Harry and his friends can prevent it. But can the momentum of WW3 be averted?

Counterstrike is a novel combining a high seas adventure, lethal international politics and a sliver of romance. Told by a master-storyteller, Hal Colebatch, Counterstrike will have you on the edge of your seat until the very end. Literally. – Coverage Report #687

BUY THIS NOVEL FROM THE PUBLISHERS HERE: http://www.acashic.com/counterstrike/

REVIEW

HAL COLEBATCH’S COUNTERSTRIKE IS A THRILLER OF IDEAS

Counterstrike, by Hal Colebatch

(Acashic Publishing, 245 pages, $23.99 paper; $19.99 e-book)

In the Information Age, a lie may be the most powerful weapon of all.

The American Spectator’s own Hal G. P. Colebatch, Australian lawyer and poet, as well as author of nonfiction books and co-author of works of science fiction, has branched out into a new subgenre of speculative fiction — a near future story focusing on the war of ideas, in his freshly released novel, Counterstrike.

The time is about five years from now. The war of militant Islam against the West continues. There has been murderous rioting in England, and Sharia Law is taking hold there. But far away in Australia, it all still seems unreal. Harry Godwin, our hero, is a lawyer and a part-time university instructor in an unnamed (but not unguessable) western Australian city. Still smarting from the break-up of a romantic relationship, he diverts himself with sophisticated war gaming along with other members of a local club, moving model ships and sailors across an elaborate board. He’s a romantic at heart, somewhat regretful that he’ll never have the chance to participate in a real naval battle.

He joins his friend Toby in what they call an “immram” (an Irish word for a sea pilgrimage, inspired, they say, by The Voyage of the Dawn Treader) to explore offshore ocean islands and do some diving from Toby’s small sailboat. En route they encounter a pair of Toby’s friends, a married couple who sail a large yacht, along with their attractive friend Leonie. They decide to all throw in together for the immram. In the course of it, Harry and Leonie are drawn to one another, though he’s gun-shy and awkward with her.

As they voyage they encounter a university research vessel carrying, among other personnel, a visiting lecturer from the United States, a Professor Sojourner, who has recently made headlines with his theory that the British government knew in advance of the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, but withheld the intelligence from the U.S., hoping to draw the Yanks into the World War II. A famous lost warship, he believes, carries proof of this betrayal.

In the course of their diving, Harry and his party discover what seems to be the wreckage of a warship of that period. Which sets them on a collision course with Professor Sojourner and the university faculty, in a battle of truth and lies that threatens the very existence of the U.S.-Australian alliance, just when both countries need each other more than they have for decades.

Counterstrike isn’t an action novel. No shots are fired onstage, no punches thrown (though there is an explosion). This Armageddon is ushered in through ideas, through words, through the mendacity of people who hate liberty, who feel a “moral” compulsion to destroy the cultural roots that nurture them in service of an ideology more powerful (to them) than loyalty or love. Some things are won, and many things are lost, but hope abides.

Colebatch is a sensitive and descriptive writer, investing his story with all his affection for his city, his country, the sea, great literature, and history. Through Harry Godwin’s eyes, we observe a sun-bright world made fragile under the threat of a thing so apparently trivial and laughable as a conspiracy theory. At one point, Harry says:

There’s a strange syndrome present. Different conspiracy theorists will very often associate with, and reinforce, one another even when they have mutually incompatible beliefs. On the 9/11 conspiracy sites one theorist who claims that a missile was fired into the Pentagon will associate himself with another theorist who claims a remotely controlled plane was crashed into the Pentagon. And how many Islamicists will proclaim simultaneously that 9/11 and the rest were great blows struck for Islam against the West and that they are part of a Jewish plot to discredit Islam and give the U.S. an excuse for invading Iraq and threaten Iran?

…Tens of thousands of people evidently think there’s something in it, “if” — magic phrase — “you keep an open mind.” I’m coming to think the truth is that if you keep an open mind people will throw all their crap in it — and as often as not have you pay them for doing so.”

Counterstrike is something like a bright photographic negative of a night scene, displaying evil through its contrast with goodness. Not only is it an enjoyable entertainment, it’s a “beat to quarters” to defend the truth, for its own sake and for the sake of all the things we cherish, that depend on freedom.

Highly recommended.

This review was published in The American Spectator and may be found here: http://spectator.org/archives/2011/05/06/hal-colebatchs-counterstrike-i

_______________________________________________

MAN-KZIN WARS X: THE WUNDER WAR

One War for Wunderland – Hal Colebatch

The story of how the first Kzinti invaders were spotted on Wunderland and how the Wunderland Government prepared for the first onslaught. This proved difficult in the light of the ARM-censored culture on war information and weaponry.

Professor Nils Rykermann, the University of Munchen’s Biologist, is called in to sit on the Wunderland Defense Council Meetings before the invasion begins in force. But despite the efforts of the Meteor Defense crews and the heroic bravery of the Serpent Swarm asteroid miners, Rykermann doubts that the Wunderland forces can keep the Kzinti at bay, and he takes to the hills to go into hiding with fellow scientist Dimity Carmody.

This is the first time that the start of the Wunderland invasion has been touched on in the Man-Kzin Wars series. This novel-length story by Hal Colebatch describes the space and ground war for Wunderland in graphic detail, and continues the cycle begun in “His Sergeant’s Honor.”

The Corporal in the Caves – Hal Colebatch

Thirty or so years into the Occupation, Kzinti forces are still mopping up the resistence of feral humans living in the Hohe Kalkstein cave system. Thought cleverly-laid traps despatched over half the kzinti squads, the surviving Kzin leader earned himself a commission and his Name, Raargh. A later attack by the cave-dwelling Morlocks forces the Kzin and remaining humans to fight as one force to survive the onslaught, forging a permanent alliance between Raargh-Sergeant and Rykermann of the Resistence.

Music Box – Hal Colebatch

After the last of the Kzinti forces on Wunderland surrendered, Raargh-Hero escaped the cities, taking with him the last surviving member of Chuut-Ritt’s family, a kit named Vaemar.

Since then, Raargh and Vaemar have been living in the wildlands, hunting their own prey and doing an odd job or two for neighbouring farmers. But with the political situation on Wunderland finally stabilising, Vaemar is in danger of becoming a political tool to lead the Kzin on Wunderland to victory again. Raargh takes him to visit Professor Rykermann – now turned politician – for his advice. Unfortunately Vaemar and Raargh are captured en route by a group of humans loyal to the memories of Chuut-Ritt.

This story also reunites Professor Rykermann with Dimity from the first story “One War for Wunderland”.

Peter Robinson – Hal Colebatch

This last story is a little hidden gem. Set during the contemporary Known Space era of the Ringworld Throne, an expedition by the Institute of Knowledge on Jinx, funded by the Puppeteers sets of to explore a recently detected slaver stasis box.

When arriving at the target, the team of explorers (including Wunderlanders, a Jinxian and two Kzinti) approach the stasis box, which is floating freely in space. Sensors detect that it is nine miles in diameter, the largest box ever discovered.

.

ONE WAR FOR WUNDERLAND

by Hal Colebatch

PROLOGUE

The ship flew in like a drunken bat, an automatic distress beacon shrieking. It did not respond to signals.

When they came within visual sight they saw it was grossly damaged, and plainly not under maneuvering control.

When they boarded the ravaged ship with its crew of crumbling, desiccated, drifting corpses, some in strange costumes, the only survivor they found was a head-injured woman in coldsleep. They slowed it and stopped it just before it entered the deadly embrace of one of the outer gas-giants.

The ship had come a long way under its autopilot from the general direction of either Sol or the Alpha Centauri System. The oddly shaven-headed man who must have instructed it as he died still floated with a freeze-dried hand on the controls.

But they tested the hull metal where they cut their way in and found that, if it had come from Earth, it must have been a very old ship before it started.

There were many dead. Far more than a normal crew. This was as packed as a colony ship, more packed, indeed, for a large part of a colony ship’s complement would have been frozen embryos. Nor did it carry the vast array of stores and supplies a colony ship would have had: almost nothing but people and hibernation cubicles and bare provisions for a skeleton crew of watch-keepers.

They were tough spacers who boarded the ship, and most had seen death in space before, but still this was especially horrible and upsetting.

Apart from the strangely costumed and coiffured men, a large number of the dead were women and children. The hibernation facilities could have just accommodated them all and looked as if these had been being prepared for use when disaster struck, but only the one had been activated.

It was easy to see but difficult to understand what had happened. It had been sudden. Perhaps the ship had accidentally crossed a big com-laser near its point of origin. A laser—a big one—had burned through the rear of the hull and opened one compartment after another to space, punching its way through hull-metal and human tissue indiscriminately. But if that was what had happened, why had the ship or the station that had fired the laser not come to its rescue?

Anyway, it had stopped short of total destruction, and a few emergency systems were still working, including the beacon that had signaled its arrival.

The damage had caused short circuits and fires that had raged even in sealed compartments until the last oxygen in the life-system was consumed. The logbook was melted slag. The last minutes of life aboard the crowded ship were better not imagined but must have been mercifully brief.

The activated coldsleep unit was damaged and operating with a backup of questionable efficiency. They took the woman down to the surface, and tugs with electromagnetic grapnels moved the strange ship into a parking orbit.

Even if the woman had not been head-injured to start with, brain-death seemed a near certainty. When they checked the brainwaves’ read-outs with their own equipment they were astonished by their strength.

They were careful, and took a long time healing her and bringing her back to consciousness. The people of We Made It were sometimes painfully aware of being a colony, without the vast medical and scientific resources of Earth or even Wunderland, but their science was still good. The robots of twenty-fifth-century nanotechnology—comparable in size to some large molecules—crawled into her brain, and when a net of them had been formed whose neural connectivity made a whole that was far greater than the sum of its microscopic parts, they sought to trigger a memory. Sensors, receptors, cognitive and motor response units more delicate by far even than those used in normal reconstructive nerve surgery linked their impulses.

It was a new technology and imperfect. The watchers saw some of what little was left of her memory translated into flickering holograms. There was a jumble of images, including, quite clearly, a scene of a sidewalk café and a man with a lopsided yellow beard under an open sky.

It looked to those who examined it like something from a picture book of old Earth, though it was not a Flatlander’s beard. The tiny robots sewed and spliced and healed a little and crawled out of her brain. They would wait before applying nerve-growth factors so new neuronic connections would not interfere further with the grossly damaged, immeasurably delicate and diffuse network of connections that created the hologram of memory.

The woman’s brain continued to puzzle them, even when they had repaired it as much as they might. There were few pictures but many abstract symbols.

They tested her DNA but that told them nothing save that she was of human stock originally from northern Europe. They brought her back to consciousness.

She could speak only in broken sentences when they began, gently, to question her in the hospital at We Made It.

In addition to this Prologue, the first seven chapters of “One War for Wunderland” can be read on the Baen Books website. Go to: http://www.baen.com/chapters/W200308/0743436199.htm?blurb

_______________________________________________

MORE MAN-KZIN VOLUMES

WITH WORKS BY HAL COLEBATCH

Copies of the Man-Kzin Wars anthologies can be purchased from Baen Books at http://www.baen.com/author_catalog.asp?author=lniven

MAN-KZIN WARS VII

The Colonel’s Tiger – Hal Colebatch

The mysterious reports from the Angel’s Pencil, detailing the anatomy and physiology of the attacking Kzin, trigger a memory of an ARM agent. After a little searching, he finds the account of a Colonel Vaughn, who battled with a “tiger man” in India during the earth year 1878.

A Darker Geometry – Gregory Benford & Mark O. Martin

This story depicts man’s first contact with the Outsiders, an event that leads to the use of hyperdrive by humans. It is a tale that has generated much controversy among Niven fans, who argue whether it can be considered “canon” or not as it sems to contradict or rewrite many of the assumptions behind Known Space (for example, it introduces the “Guardian” caste of Puppeteers, who seem to go against everything Niven wrote about the cowardly species).

Prisoner of War – Paul Chafe

A surveillance trip into the Sol system by the Kzin scout ship Silent Prowler ends in disaster after a cat-and-mouse chase with the earth destroyer Excalibur. The Kzin Fleet Commander is the only survivor and is taken as a prisoner of war.

MAN-KZIN WARS VIII

Choosing Names – Larry Niven

Short story about a captured telepath, who demands his own Name in the wake of the first Kzin attack at Sol.

Telepath’s Dance – Hal Colebatch

A sequel to Niven’s “The Warriors,” exploring what happened to the Angel’s Pencil.

Galley Slave – Jean Lamb

When the Kzinti take over of a patrol ship in the vicinity of earth, a female computer programmer helps to defeat the invaders by reprogramming the food synthesizers to weaken her foes.

Jotok – Paul Chafe

A story of a Jotok scout coming to a pre-civilized Kzin world. Very insight on early Kzinti civilization.

Slowboat Nightmare – Warren W. James

Another story about a slowboat taken over by a Kzin ship. The few human survivors must use every resource and weapon, and all their monkey cleverness, to take on the Kzin crew.

MAN-KZIN WARS IX

Pele – Poul Anderson

This is Poul Anderson’s last published story; it first appeared in Analog Science Fiction Magazine right around the time that he passed. In this sequel to “Inconstant Star” the star Pele, thirty light years from Earth, is about to undergo a major cataclysm: a 10-Jupiter mass gas giant is about to be absorbed by the star. As the planet “Kumukhahi” begins its deadly spiral, science ships from Earth and Kzin and a passenger ship containing Tyra Nordbo arrive to witness the destruction. Of course the dishonoured Kzin “Chrul-Captain” just can’t resist being a hero and uses a prototype ship to get right in the middle of the action.

His Sergeant’s Honor – Hal Colebatch

Set during the last days of the Kzin occupation of Wunderland, “His Sergeant’s Honor” tells the story of Raargh-Sergeant, who defends the life of a collaborator who has been branded a traitor by the Provisional Free Wunderland Government, all for a sense of honor.

Windows of the Soul – Paul Chafe

Captain Joel Allson of the ARM has a murder on his hands when a dismembered body is found in a transport tube on the asteroid/space station world of Tiamat. Man and Kzin make strange bedfellows in this noir-ish detective thriller.

Fly-By-Night – Larry Niven

Larry’s newest Known Space short story returns us to the adventures of one of its favourite characters, Beowulf Shaeffer, ex-pilot, adventurer and one of Larry’s popular “space tourists.”

Set after the events of “Procrustes” (see the colection Crashlander), Shaeffer finds himself onboard a passenger ship, the Odysseus, just as it is being captured by a ship of Kzinti pirates. Shaeffer is taken prisoner and develops an unusual alliance with a non-practising Kzinti Telepath, “Fly-by-Night” and his octopus-like Jotoki slave, “Paradoxical”.

MAN-KZIN WARS XI

Three at Table – Hal Colebatch

Arthur Guthlac, a survivor of the Occupation and Liberation of Wunderland, discovers a mysterious woman and a wounded Kzin living in the wilderness.

Grossgeister Swamp – Hal Colebatch

Vaemar, last survivor of Chuut-Riit’s bloodline, investigates a rash of disappearances and uncovers a horrifying secret deep in a Wunderland swamp.

Catspaws – Hal Colebatch

Colebatch’s cast of characters—Vaemar, Nils Rykerman, Raargh, Arthur Guthlac and Dimity Carmody—encounter a Protector created from Wunderland’s cave-dwelling Morlocks.

Teachers Pet – Matthew Joseph Harrington

Fleeing the Kzinti, Peace Corben turns her stolen ship towards the failed colony planet of Home and discovers the real reason the world was abandoned. (Read the story all the way through to learn more about the spread of the Kdaptist sect among the Kzin.)

War and Peace – Matthew Joseph Harrington

Now a Protector, Peace Corben meddles in the later Man Kzin Wars in subtle and not-so-subtle ways.

The Hunting Park – Larry Niven

A group of Kzin ambassadors gain valuable insight into humanity when they barely survive an African safari.

MAN-KZIN WARS XII

Echoes of Distant Guns – Matthew Joseph Harrington

This introductory chapter is really three seperate vignettes set around the dawn of the Man-Kzin Wars. The first concerns Kzinti and the Grogs, the next the ARM, and the last the Smart (a race called the Pierin).

Foreign Legion – Hal Colebatch and Matthew Joseph Harrington

The Jotoki unleashed the Kzinti on the universe by employing them as mercenaries. Later they “recruited” a Roman Legion from Earth to help in the fight against the Kzinti. Centuries later, the descendants of that legion (and the Jotoki who brought them) are discovered on a distant Kzin colony world by a human who wants to bring them home.

The Trooper and the Triangle – Hal Colebatch

A short story of a Kzinti warrior who doesn’t fit in.

String – Hal Colebatch and Matthew Joseph Harrington

In this sequel to “Peter Robinson,” Richard and Gay Guthlac and Charrgh-Captain encounter a Slaver stasis box with quite unexpected contents.

Peace and Freedom – Matthew Joseph Harrington

Peace Corben returns. The smart-alec Protector recruits a small army of humans, as well as the young kzintosh Shleer, to fight a Thrint and his Tnuctipun thralls.

Independent – Paul Chafe

A single-ship pilot accused of killing his passenger remembers nothing about the trip and is forced to team up with a vengeful Kzin to clear his name.

The above summaries of the stories and novellas that make up the various volumes of the Man-Kzin Wars have been reproduced from Larry Niven’s website at http://www.larryniven.org/kzin/reviews.shtml

RETURN OF THE HEROES

Click here to read Andrew’s review of Hal Colebatch’s Return of the Heroes.

CONTACT HAL COLEBATCH

Hal is Andrew’s friend. You can contact him through Andrew. Send an email to Andrew and he will forward it to Hal.